The Trust has recently responded to the public consultation on the North East Active Travel Strategy. The proposed strategy aims for active travel to become the natural first choice for short everyday trips and combine it with public transport for longer journeys. To achieve this it outlines plans for a major package of investments in the region’s walking, wheeling and cycling network.

The Trust has made a detailed response which can be seen on the Consultations page. Additionally, in 2022, the Trust made a response to a consultation on ‘Active Travel England’’s role in the spatial planning system.

Twenty-five years ago the final report of the Durham City Travel Study was released. It was commissioned by the County Council to recommend how to provide “an environmentally friendly and sustainable transport system which meets future economic and social needs in an effective manner”.

The final report came out a few weeks after Labour’s landslide victory in the 1997 general election. Later that year the Kyoto Protocol, the first to include specific carbon reduction targets, was agreed. In the last days of the Major government, in the wake of protests against the Newbury Bypass, the Road Traffic Reduction Act was passed, which gave the Secretary of State for Transport the power to require local councils to prepare assessments of local road traffic and targets for reductions. These powers have never been used, and the transport sector has made almost no contribution to reducing carbon emissions.

In the local context, plans for a Western Relief Road had recently been dropped from the Department of Transport’s National Programme. The county Structure Plan envisaged the reopening of the Leamside Line, and included a Northern Relief Road together with a link from the Pity Me roundabout to the A691 at Witton Gilbert. The “Through Road” in Durham City centre was carrying 40,000 vehicles a day and the “growth of the university and expansion of tourism” had contributed to local travel demand.

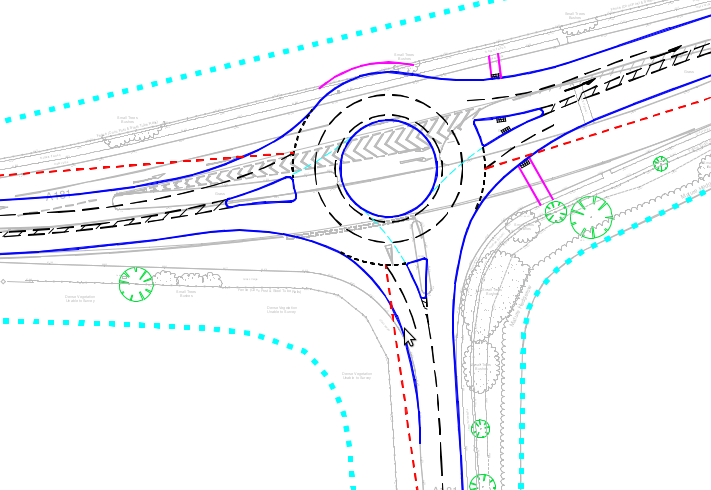

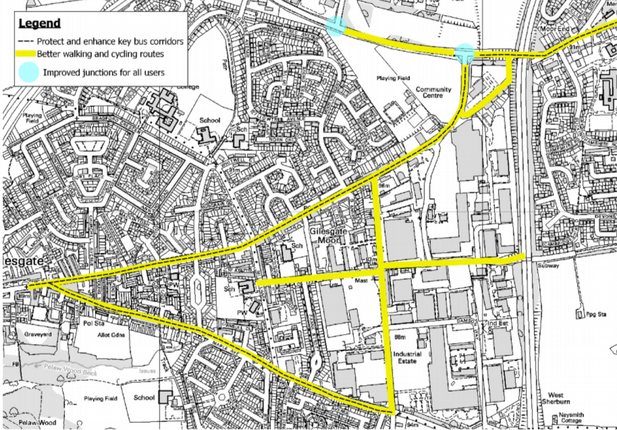

This may all sound rather familiar, but on reading the report we are quickly reminded of many fundamental differences. The report recommends establishing Park and Ride services, a Controlled Parking Zone in the city centre, and permit-controlled access to Saddler Street and the peninsula, where the university still allowed car parking on Palace Green. Signalising the Gilesgate, Milburngate and Leazes Bowl roundabouts is proposed, while at the time of the report North Road was open to north-bound traffic along its whole length. Bus priority schemes included adding bus lanes to the A690 from Carrville to Gilesgate roundabout and on High Carr Road and Dryburn Road approaching the city centre from Framwellgate Moor.

The report included an outline programme, in which the key recommendations would have been implemented between 1997 and 2001, but it inevitably slipped. The first controlled parking zones, in the Elvet area, became operational in October 2000. The restrictions on access to the peninsula were implemented as the UK’s first congestion zone in October 2002, and the three Park and Ride services were running by December 2005, six years later than planned. The Gilesgate and Leazes Bowl roundabouts were not signalised until 2016.

Other proposals have not been taken forward. A Park and Walk site, converting one of the Chorister School playing fields on Quarryheads Lane into a car park to serve the Cathedral, would have been very damaging, even if it had been softened with what the consultants termed “National Trust” type landscaping! On the other hand, there were many practical suggestions for improving walking and cycling which have not been carried out, including footway widening on Quarryheads Lane and Church Street and a pedestrian crossing at the bottom of Station Approach. It is not clear how much work was done on “Safe Routes to School” – children attending St Margaret’s School still rely on a crossing patrol, rather than a signalised crossing, for example. A toll on Milburngate Bridge traffic was controversial, and would have required new powers from central government.

The report suggested that if each employee currently travelling by car used another mode one day a week, a reduction in car travel of 20% could be achieved. This will no doubt be suggested again, but it is foolish to rely on public co-operation without any incentives.

Although the Controlled Parking Zones were implemented, the report envisaged a rather different approach to managing car parking in the future, including using planning controls to encourage reductions in private non-residential parking, and the use of pricing to severely limit long-stay parking in the city centre. The proper management of car parking is described as “key to the future of the DCTS” (Durham City Travel Study) and is designed to “increase the supply of short-term spaces for visitors, shoppers and the disabled” as well as assist the introduction of cycling, walking and bus priority measures. With the current flat half-hourly charges, and free parking in the afternoons, there are many streets in the city where these aims are not being achieved. It is likely that the bus lane that the report proposed on the north-bound side of New Elvet would have required removal of car parking, and many of the suggestions for the cycle network might also have conflicted with parking spaces. The Durham City Sustainable Transport Delivery Plan, adopted in 2019, noted the problems caused by free parking at major employers (including the County Council and the university), and judged the on-street parking charges as low compared to other historic towns. But the Delivery Plan does not include the level of detailed analysis and data behind the 1997 study. A review of the management of car parking in Durham is long overdue.

Overall, the 1997 report was highly influential, and shaped a lot of the traffic management measures we see in Durham today. The Park and Ride services and the congestion zone have been successful. If the walking, cycling and parking management measures in the report had been fully implemented, and less effort been wasted on planning relief roads, Durham would be a safer, cleaner, and altogether more liveable city. It is clear that these areas should be given much greater priority in the future.

Over the last 25 years, even as car ownership and congestion has risen, local people have continued to demand better transport, with the Trust playing a significant part. There are two petitions live on the Council’s website at present relating to traffic on Lowes Barn Bank and Shincliffe. Will the Council continue to shrug its shoulders and do very little, or can the new joint administration drive through a change in approach? While central government has been somewhat chaotic of late, there is a renewed impetus in national policy towards sustainable transport. In his first Prime Minister’s Questions, Rishi Sunak was asked about safety for school children, and highlighted how local authorities can reduce speed limits and create school streets to restrict motor traffic at busy times. Durham County Council has started reducing speed limits round schools, but restricting access has not yet been tried.

When we look back in another twenty-five years, will we recognise this period as being the start of a dramatic improvement in how we travel around our city and county? Or will we regret the missed opportunities? Probably, like this review of the 1997 plan, it will be a bit of both.

Last week Durham County Council’s cabinet formally adopted a Local Cycling and Walking Infrastructure Plan for Durham City. The aim of an LCWIP is to identify the core walking and cycling networks to be developed or improved. Having an LCWIP in place makes it easier to bid for central government funding.

Two trustees were among those invited to a stakeholder session in January 2020, when the plan was under development, and is good to see that the consultants took some of our comments on board in the final plan. It is also welcome that County Council has secured Department for Transport (DfT) funding for preparing LCWIPs for a further nine towns.

The Trust has concerns about some of the details of the plan, but also, more generally, about how the plan will be applied and whether the various Council departments will be able to work together to make the most of the opportunities to invest in walking and cycling. We intend to submit a formal response to the Council, but would be very glad to consider comments from members before the final response is prepared.

The broader concerns fall under the following headings

- the delivery of network improvements beyond the LCWIP area

- reliance on shared use facilities for walking and cycling

- delivery of the priority routes, particularly the handing of changes to Church Street

- ensuring that planning officers give sufficient weight to sustainable transport

- co-ordination of road renewal and other highways works with walking and cycling improvements

Comments on proposed cycle network

Within the confines of the identified area, the proposed network is reasonably comprehensive, but there are some changes that the Trust hopes can be incorporated.

The alignment of the Northern Relief Road, which was rejected by the Inspector at the Examination in Public of the County Plan should be deleted from the network map, and replaced with a route crossing the Belmont Viaduct.

There are no connections shown to the west of the A167 at Stonebridge, despite this falling within the LCWIP area. Neville’s Cross Bank and Lowes Barn Bank are both important connecting routes which should be added.

Comments on proposed walking network

The rationale behind the walking network map is less clear. It seems to be very much focussed on the city centre, so walking routes to the shops and employment areas in Framwellgate Moor and Newton Hall are absent, as are any routes east of the A1(M), for example to the Belmont Industrial Estate. A secondary route through Flass Vale, emerging on the A167 close to Durham Johnston School has been identified, but Redhills Lane and the A167 itself, both of which are heavily used by pupils at that school, do not feature on the map. The access road on the north side of Aykley Heads is another surprising omission.

While the purpose of an LCWIP is primarily concerned with everyday journeys, in the context of the city’s heritage the significant former pilgrim routes make an important contribution to the physical structure of the city. Local people and those visiting the city use them for access from within and beyond the LCWIP area. As well as identifying more of these routes on the walking network map, the relationship between the LCWIP and the Rights of Way Improvement Plan (ROWIP) could be better articulated.

The overview of priority walking interventions in Table 5-1 seems to largely repeat Table 4-1 which covers priority cycling interventions. Some of the proposals in Table 5-1 are even on routes which are not shown on the pedestrian network map. A “shared use path on Broomside Lane” could arguably worsen the walking environment.

The Trust would urge the Council to avoid wherever possible further designation of urban footways as shared use paths. These are strongly discouraged by the LTN 1/20 guidance. It is likely that e-scooters will be legalised, and that e-bikes will become more prevalent, matching take-up in other European countries. Safe space separate from motor traffic which does not conflict with pedestrians will be crucial to the successful take-up of these new options.

Shared use may be appropriate on routes with low pedestrian footfall, but the routes in Table 5-1, identified as the priority for investment, are surely not in this category. Short stretches of shared use provision may be necessary if there is no other way provide safe cycling access, but reallocation of carriageway space and reduction in motor traffic volumes should be resorted to in preference.

Many current issues for pedestrians around the city are in the details of provision, such as narrow pavements and poor crossing facilities. A more balanced priority list might have included remedial work at a number of such locations rather than concentrating on a single route. The Durham City Neighbourhood Plan Working Group produced a paper on walking and cycling issues which included such details. While this previous work only covers part of the LCWIP area, it might serve as a starting point for the creation of a database of pedestrian issues throughout the LCWIP area. Such a database would have a number of uses:

- making it easier to identify improvement schemes which could be delivered as low-cost add-ons to regular renewal works such as resurfacing

- assisting planning officers in identifying opportunities for funding from planning applications, both at the pre-application stage and when determining applications

- providing evidence of the need for improvement to counter over-optimistic transport assessments submitted by developers

LCWIP area

DfT guidance suggests that cycling can replace car journeys of up to 10km. It is unfortunate that the LCWIP area was so tightly defined, as it omits significant residential and employment areas which are well within this radius, such as

- Brandon

- Meadowfield

- Ushaw Moor

- Bearpark

- Sherburn

- High Shincliffe

One of the key journey generators, Durham Johnston School, is on the very boundary of the LCWIP area. Part of the County Plan housing allocation at Sniperley lies outside the LCWIP boundary.

Can a light-touch revision of the LCWIP be carried out within a couple of years, to expand the scope formally to include these areas? If these areas are not included, will it make it harder to obtain funding from developers and the DfT?

Delivery of priority routes

Walking and cycling routes from South Road via Church Street and New Elvet to Gilesgate and Broomside Lane have been prioritised for investment in the plan, partly because of the high student flows on this axis. The ideas for Church Street include a 20mph limit, pavement widening, and removal of some car parking. The removal of parking spaces could be very contentious. The Trust is also sceptical that a 20mph zone will have any effect without active enforcement and a reduction in traffic volumes. Cycling participation is unlikely to be increased without protected space.

It is clear from the concerns about removing parking spaces that the current situation is unsatisfactory, and that better management of spaces is needed. Perhaps short-stay car parking spaces could help to serve the businesses on Church Street, as well as helping social care providers visiting residents. The longer-stay parking needs to be examined. It is likely that a proportion is being used by students travelling relatively short distances to the university. Working with the university to reinforce the university’s travel plan and reduce the use of cars by students would be beneficial. The DfT’s statutory guidance to highway authorities published in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic continues to recommend reallocation of road space to walking and cycling, including “school streets”, restricting motor traffic at pick-up and drop-off times during term.

Given all the competing demands, the Trust would like the future of Church Street, Hallgarth Street and Whinney Hill to be considered together holistically. Bringing in urban design expertise and proper engagement with stakeholders would help achieve a better balance.

The LCWIP and planning applications

While the LCWIP is vital for bidding for central government funding, it also has a role in obtaining contributions from developers, being referenced in County Durham Plan Policy 21. The Trust is concerned that the needs for sustainable transport improvements are not currently given sufficient weight by officers when assessing planning applications. The conditions on approval of the housing development at Bent House Lane, for example, involved contributions towards work on five road junctions. Cycling and walking improvements were not the impetus behind the proposals: the emphasis was entirely on accommodating additional motor traffic from the development. The developer had, in fact, offered Section 106 money towards bus, walking and cycling schemes mentioned in the Durham City Sustainable Transport Delivery Plan, but this was not taken up by the planning officer.

Highway authority comments on planning applications are often concerned solely with accommodating motor traffic. The council has a statutory duty to secure “the expeditious movement of traffic on the authority’s road network”, but the Act specifically states that “traffic” includes pedestrians. The duty is qualified by a requirement that the authority also have regard to their other obligations, policies and objectives. Relevant here are the council’s Strategic Cycling and Walking Delivery Plan, the Durham City Sustainable Transport Delivery Plan, and the need to improve air quality and enable the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions.

The Trust would therefore like to see far greater weight given by planning officers to the delivery of sustainable transport.

Value for money

The LCWIP seems to be relatively pessimistic about how long it will take to deliver the walking and cycling networks to the appropriate standard. Where funding is scarce the Council needs to make sure that every opportunity is taken to make improvements in the course of carrying out other work. The LCWIP proposes stepped cycle paths on New Elvet and changes to arrangements at the traffic lights both at the top and bottom of that street. This street has recently been resurfaced, with new road markings, traffic islands and lights being installed matching exactly what was there before. Why were the cycle lanes not constructed at the same time?

There have also been resurfacing works on Church Street, the A690 near Sutton Street, and the A690 at the top of Crossgate Peth in the last two years. In each of these locations widening the pavements, realigning kerbs, or better crossing facilities could have been carried out.

We would like to see the Council consult with local groups and parish councils well ahead of any programmed resurfacing work, to ensure that walking and cycling improvements are identified and can be delivered more cost-effectively.

There is also scope for cheaper interventions, such as modal filtering or partial road closures, in some parts of the city. The Trust would like to see the LCWIP developed to cover such ideas. There is a need for a much greater pace of change in order to support the levels of modal shift which are now required in the face of the climate emergency.

In the previous posting we saw how the government’s acceptance of the Sixth Carbon Budget necessitates a major reprioritisation of our transport spending locally. Since declaring a climate emergency in February 2019, can we see evidence of the County Council making radical changes to how transport-related developments are designed and assessed, or is it still “business as usual”?

The County Durham Plan, adopted in the autumn of 2020, allocates sites around the county to meet the need for housing. Two sites on the edge of Durham City were removed from the green belt in order to make the land available for housing. The County Council justified the removal of green belt protection partly on the basis that sites beyond the green belt would be less sustainable. It was argued that building on green belt land adjacent to the city would enable residents to walk, cycle and use public transport for a greater proportion of their journeys.

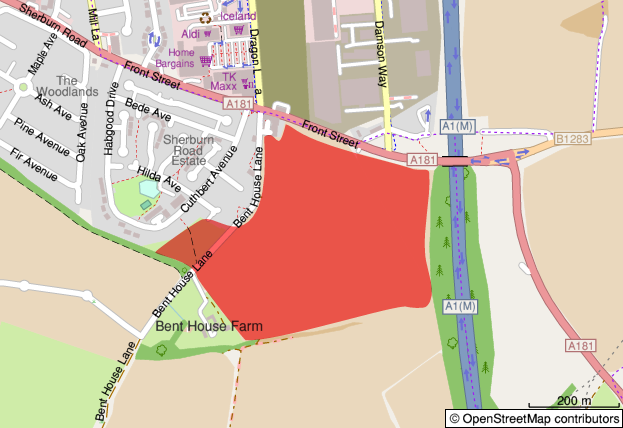

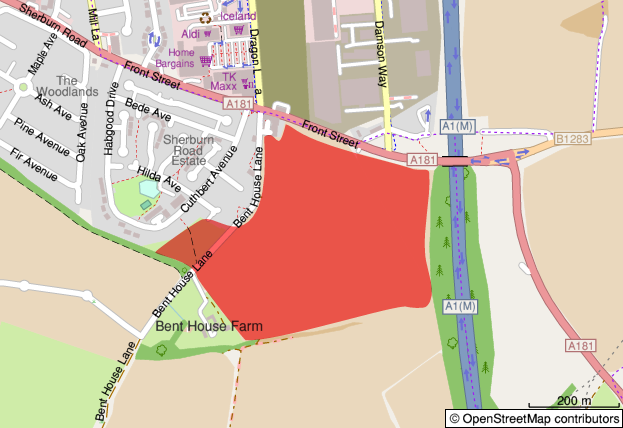

Bent House Lane housing site

In November 2020 Banks Group, which owns most of the Bent House Lane site, submitted an outline planning application, DM/20/03558/OUT. This seeks to establish broad principles for the layout of the site, including a design code, and addresses access to the site including transport impacts and mitigations.

Bent House Lane site location

The Trust considers there is room for a great deal of improvement in the planning application, and that the application does not satisfy the County Plan policies in its present form. But rather than discuss details such as the landscape aspects, the road access to the site, or the relocation of the bus stops, I want to examine and challenge the assumptions behind the approach to the transport impacts taken by the developer and the Council.

Major planning applications are accompanied by a Transport Assessment (TA). Developers hope that the consultants employed to write the TA will be able to demonstrate that any highways impacts can be accommodated within the existing infrastructure, absolving the developer of any need to pay for improvements. In the case of the Bent House Lane application, seven junctions were assessed and modelled. An estimate of likely commuting destinations was produced, using 2011 census data. (Note that commuting only represents 20% of trips nationally, so this method will be flawed in relation to peak time education trips.) Traffic counts were combined with forecasts from the National Transport Model to estimate the likely flows in 2030, with and without the housing development going ahead. Of the junctions studied, in four cases the additional traffic generated by the development would, by 2030, exceed the capacity of the junction:

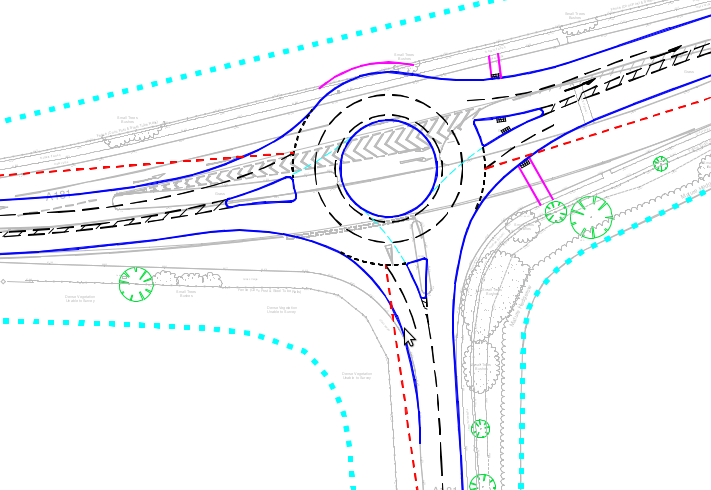

For three of these, the mitigation proposed is to convert the junctions to roundabouts, or to add traffic signals or extra lanes to accommodate the growth.

Proposed roundabout at the A181/B1283 junction to the east of the site

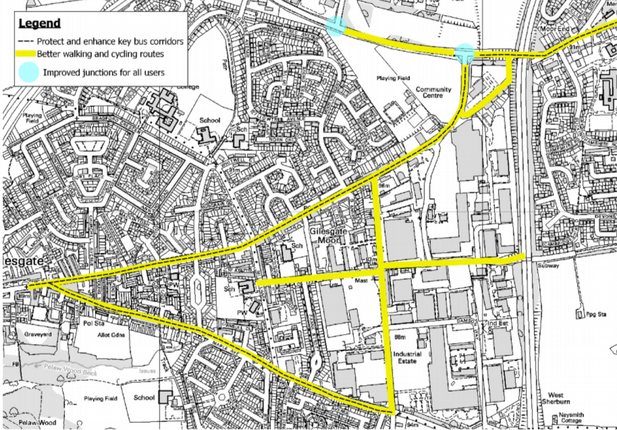

At the meeting of the A181 and the Sunderland Road there is no room to enlarge the junction, and instead the developer indicates a willingness to contribute funding towards walking, cycling and public transport improvements along the A181 and Sunderland Road corridors into Durham City, and the assessment refers to routes identified in the Durham City Sustainable Transport Delivery Plan. I have to confess that when helping to prepare the Trust’s responses to the application, I did not spot this offer of investment in sustainable transport in section 8.5 of the Transport Assessment. While detailed plans have been submitted for the remodelling of the other junctions, there are no plans covering walking or cycling improvements on the A181 or Sunderland Road. Perhaps the developer is relying on the Council’s preparation of the Local Cycling and Walking Infrastructure Plan (LCWIP) which is expected to be presented to the cabinet in June?

Map from Durham City Sustainable Transport Delivery Plan with roads requiring walking, cycling and public transport improvements highlighted.

Despite the lack of detail, the TA concludes:

Following the implementation of sustainable transport measures of these types, it is considered that the residual impact of the proposed development on the operation of the highway network will be immaterial.

There is no evidence given to support this view. The application lacks detailed plans, evidence or modelling of the alternatives to motor traffic growth. This sadly reflects the importance assigned to motor traffic flow in contrast to sustainable transport by most developers and local authorities. There is a whole industry built around the problems posed by growth in motor traffic, with specialist software, survey techniques, and design solutions which highways engineers will instinctively reach for. But remember! – the Sixth Carbon Budget requires us to steadily reduce the amount of car traffic year by year by about 3% for the foreseeable future. The National Transport Model, which the applicant draws on for the forecast growth, does not yet reflect this. It is a “predict and provide” model based on laissez-faire transport policies which are not equal to tackling the climate crisis.

The Transport Assessment acknowledges (para. 7.7.4) that “traffic growth forecasts at both a national and a local level have historically tended to significantly overestimate growth”. It also notes that changing patterns of work and employment, hastened by the pandemic, are likely to flatten the peak demand. But in order to come to a “robust” assessment, neither of these uncertainties have been factored in. Still less has the need to actually reduce, in absolute terms, traffic levels.

The result is that the planning application, as currently formulated, envisages large-scale works at two or three road junctions to accommodate traffic growth which the application acknowledges is likely to be overestimated – traffic growth which needs to be reversed to meet our climate commitments. These have been prioritised over unspecified improvements for sustainable transport, the effectiveness of which has not been quantified.

Planning policy and the climate emergency

If the Council is serious about prioritising sustainable transport, as it has claimed in various policy documents, then the planning authority should be requiring a much higher standard of analysis from developers, and the highway authority should take a sustainable-first approach to mitigation of the impacts. The expectation can be set by the Council at the pre-application stage.

Most development proposals have some downsides, and determining whether an application should be approved is a matter of balancing different policies and needs. To do this, planners and planning committees have to judge how much weight to give when an application does not fully comply with a policy by comparison with any benefits that will result. I would argue that in the context of the climate emergency, where we have to make a transition in transport “like none we have attempted before” (to quote Professor Greg Marsden), considerable weight needs to be given to the planning policies which favour sustainable transport.

Many developers quote from National Planning Policy Framework paragraph 109 which states that

Development should only be prevented or refused on highways grounds if there would be an unacceptable impact on highway safety, or the residual cumulative impacts on the road network would be severe.

The wording in earlier versions of the NPPF referred to “transport grounds” rather than “highways grounds” and developers and the Council sometimes still use the old wording. The change, however, was deliberate and significant. It signifies that development may be refused on various other transport grounds, such as poor provision for sustainable transport, without there necessarily being severe residual impacts on the road network.

What would a sustainable approach look like?

The initial focus should be on the Transport Assessment and any associated mitigations. Most Transport Assessments follow a common pattern, and a standard aspect to include is an assessment of the accessibility of the site by different modes. In the Bent House Lane application, five pages describe the current walking, cycling and public transport networks around the site, and another five pages access the accessibility of local amenities by these modes. The analysis is often quite superficial: for example, as with many other Durham City applications, the section on cycling is keen to mention National Cycle Network Route 14 with its connections to Darlington via Hartlepool and South Shields via Consett, but is silent on the lack of dedicated provision for realistic local journeys.

By contrast, forty-one pages of the main report cover the highway network and the assessment of the junctions. These are supplemented by another 300 pages of appendices which are entirely devoted to motor traffic surveys and modelling.

A sustainable-first approach would also include a qualitative assessment of the pedestrian and cycle network, and would recognise that existing provision may be sub-standard. This need not be any more onerous than the traffic surveys and modelling. For example, there is a simple junction assessment tool in the new government guidance, Cycle Infrastructure Design LTN 1/20 (p. 178), which could be applied to each junction a cyclist would have to pass through to reach the local amenities, schools and employment sites. Most of the junctions around Bent House Lane would score very badly.

Improvements to the walking and cycling infrastructure could then be proposed. The Department for Transport sponsored Propensity to Cycle Tool would be consulted, demonstrating the potential for 17% of commuter journeys to be cycled, given good-quality routes. Such routes might parallel the main road routes, but there is also the opportunity to give sustainable transport a significant advantage by providing short-cuts. For example, from Bent House Lane the Elvet area and the university campus at Mountjoy could be reached via riverside paths. Liaison with local schools might identify other barriers to sustainable travel noted in their school travel plans.

For public transport a simple table of the service frequencies and destinations would not be sufficient: there needs to be a demonstration that journey times would actually compete with alternative modes. Bus priority measures could then be proposed and funded. There would be evidence of engagement with public transport operators.

Conclusion

Planning applications are determined according to the local County Durham Plan, which itself accords with national planning policy, and the change of administration at County Hall does not change this. But the weight accorded to policies – what is judged important, and where compromise can be accepted – is to some extent a political decision. And it is absolutely the preserve of the Council as highways authority to judge what is acceptable in terms of transport mitigations. The applicant has demonstrated that there are transport impacts which require mitigation, and the new administration could insist that major works to increase motor traffic capacity at junctions should be the last, not the first resort.

By prioritising sustainable transport interventions, not only would a greater proportion of the new residents’ journeys be by sustainable modes, but other people would benefit from the improvements, in turn freeing up capacity on the surrounding road network and reducing the need for motor traffic growth to be accommodated. The aim should be to avoid the need to commit any funding to road “improvements” because these will become frozen assets (or white elephants) if we are successful in reducing demand in response to the climate emergency.

Further reading

If you are interested in more information on the Bent House Lane application, the Trust submitted an initial response to the planning application in January. Pages 4-6 summarise the transport objections, which are set out in detail on pages 13 to 35. A further response was submitted in March which covers public rights of way, road junctions and bus stops.

The full documentation can be found on the County Durham online planning application system by searching for reference DM/20/03558/OUT.

See our previous post on this topic.

It may be a while before the full implications of the change of administration at County Hall become apparent, but what is already clear is the scale of change which is required in transport policy. As reported by the BBC in April the government accepted the advice of the Climate Change Committee, and the targets of the Sixth Carbon Budget, published in December, will become law. We now have a commitment to cut UK emissions 78% by 2035. Emissions from surface transport, which accounted for 22% of total UK emissions in 2019, have remained largely flat since 1990. We now have to cut emissions by between six and ten percent per year every year, and because there is a budget, a limit to the total amount of CO2 which can be emitted if we are to avoid substantial planetary warming, if we start cutting slowly we will quickly fail.

At the Westminster Energy, Environment & Transport Forum policy conference on 30 April the opening talk was given by Professor Greg Marsden of the University of Leeds, Director of DecarboN8, a research group of academics at northern universities including Durham. Durham County Council is listed as one of the project partners. Professor Marsden placed the emissions targets into context. The whole 15 minute talk is worth watching on YouTube. Some matters, such as fuel duty and public transport costs, are beyond the influence of local government, but key points for us to consider locally include:

- Moving to electric cars will only provide 36% of the reductions we need up to 2029. A further 30% of the savings are proposed to be found through demand reduction.

- We ought to use light electric mobility, not cars, for a lot of journeys.

- Putting new developments in car dependent locations will make matters worse.

- Local transport spending has halved in the last 20 years.

Professor Marsden said that this has to be a transition like none we have ever attempted before and “if it’s not uncomfortable, then it probably isn’t going far enough or fast enough”.

What does this mean for Durham County Council?

Demand reduction

The need for demand reduction of about 3% every year for the next decade means that virtually any proposals that involve accommodating additional motor traffic are counterproductive. Proposals for increasing the number of lanes on the A167 between Neville’s Cross and Sniperley, for example, will not only encourage additional traffic, but the costs will eat into the very limited local transport budgets that we desperately need to spend on enabling people to find alternatives to car travel. No doubt there will be readers of this article who will find their journeys a little quicker if road widening is carried through, but such “improvements” are clearly unsustainable.

To allow those who genuinely need to drive to continue to make their journeys, we need to ensure that the majority of shorter journeys, perhaps as many as 1 in 3 in urban areas, switch to less polluting forms of travel. To do this we have to invest in sustainable transport, not roads. The improvements in public health, air quality, and the quality of our public spaces that will result will benefit us all.

Housing developments

The County Council may hope to obtain some funding towards transport infrastructure, via Section 106 contributions, from the housing developers of the Sniperley and Bent House Lane sites. These sites were released from the green belt on the understanding that they were more sustainable than the alternative of building houses beyond the green belt.

The Council must ensure that these contributions go towards improving walking, cycling and public transport links to the surrounding neighbourhoods and the city centre, so that the proportion of the new residents travelling by car is lower than the current averages.

Making best use of limited resources

With local transport funding at such low levels, every penny that the Council spends has to contribute to a positive change. We cannot afford to spend money on transport projects which do not actively reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The time and money being spent on the Sands Public Inquiry in order to defend appropriation of ancient common land in order to build a car park for councillors, in what is said to be one of the most accessible locations in the county, is a sorry example of the Council’s wrongheadedness.

The North East has made a bid for central government funding to deliver a new North-East Transport Plan. Funding has not yet been confirmed, but the Trust’s response to the consultation approved of the broad aims of the plan but found the proposals for achieving them woefully inadequate.

Officer time is also a vital resource. The County Council has spent most of the last decade preparing and promoting two iterations of the County Plan which were predicated on green belt release for housing yielding funding for the Western and Northern Relief Roads. Each time, at the Examination in Public, the appointed Planning Inspectors accepted the evidence of the City of Durham Trust and other local campaigners and deleted the relief roads from the plans. Highways officers who have habitually looked for solutions to accommodate increased motor traffic must now be redirected to designing schemes for bus and cycle lanes, and improving the streets for pedestrians. If traffic levels are going to reduce, and reduce they must, there will be more scope to reallocate roadspace to sustainable transport. Where there is insufficient space to provide dedicated lanes, the Council should consider restricting access to through traffic or reducing speeds.

High in the Council’s priorities must be the creation of Local Cycling and Walking Infrastructure Plans (LCWIPs) which will help the Council bid for central government funding. Two Trustees took part in the stakeholder event for the Durham City LCWIP in January 2020, but we have not yet seen the resulting plan. It is due to be presented to Cabinet in June along with LCWIPs for Chester-le-Street and Newton Aycliffe. Those for the other main towns must be accelerated.

A challenge

Durham County Council declared a climate emergency in February 2019. The Sixth Carbon Budget sets out demanding reductions in both emissions and in traffic levels which have to be achieved. As the Trust pointed out in its response to the Parking and Accessibility SPD consultation, “to achieve changes of such magnitude, Durham County Council will need to use every tool available. Most interventions will take time to produce results and we have no time to waste”.

Let us hope that the new administration which emerges from the recent elections has the energy and political will to see through changes which, to use Professor Marsden’s phrasing, may be uncomfortable, but which go both far enough and fast enough.

In further articles we intend to look in more detail at recent planning applications and consultations which illustrate the change in mindset which will be required to meet this challenge.

See our next post on this topic.

The goverment is providing councils with emergency active-travel funding to ceate temporary interventions to make walking and cycling possible and safe under social distancing requirements. Durham County Council is carrying out a consultation to identify areas that need attention: Street Space in County Durham. The Trust has submitted their response.