Transport priorities for Bent House Lane

In the previous posting we saw how the government’s acceptance of the Sixth Carbon Budget necessitates a major reprioritisation of our transport spending locally. Since declaring a climate emergency in February 2019, can we see evidence of the County Council making radical changes to how transport-related developments are designed and assessed, or is it still “business as usual”?

The County Durham Plan, adopted in the autumn of 2020, allocates sites around the county to meet the need for housing. Two sites on the edge of Durham City were removed from the green belt in order to make the land available for housing. The County Council justified the removal of green belt protection partly on the basis that sites beyond the green belt would be less sustainable. It was argued that building on green belt land adjacent to the city would enable residents to walk, cycle and use public transport for a greater proportion of their journeys.

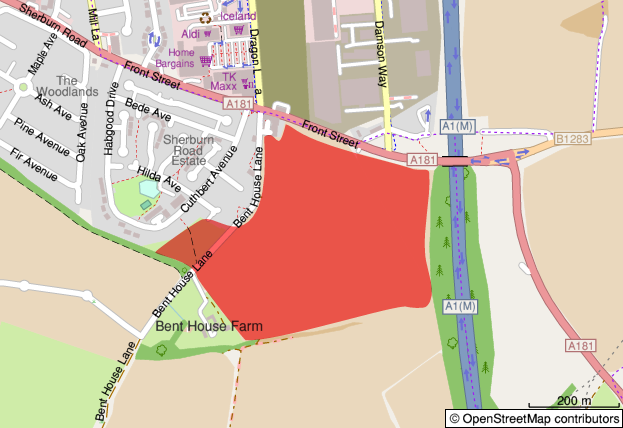

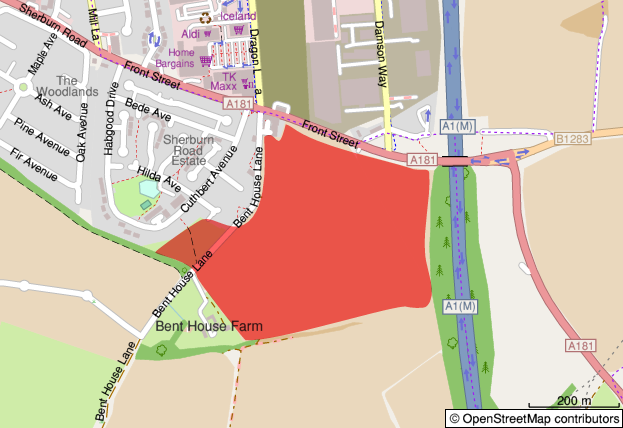

Bent House Lane housing site

In November 2020 Banks Group, which owns most of the Bent House Lane site, submitted an outline planning application, DM/20/03558/OUT. This seeks to establish broad principles for the layout of the site, including a design code, and addresses access to the site including transport impacts and mitigations.

Bent House Lane site location

The Trust considers there is room for a great deal of improvement in the planning application, and that the application does not satisfy the County Plan policies in its present form. But rather than discuss details such as the landscape aspects, the road access to the site, or the relocation of the bus stops, I want to examine and challenge the assumptions behind the approach to the transport impacts taken by the developer and the Council.

Major planning applications are accompanied by a Transport Assessment (TA). Developers hope that the consultants employed to write the TA will be able to demonstrate that any highways impacts can be accommodated within the existing infrastructure, absolving the developer of any need to pay for improvements. In the case of the Bent House Lane application, seven junctions were assessed and modelled. An estimate of likely commuting destinations was produced, using 2011 census data. (Note that commuting only represents 20% of trips nationally, so this method will be flawed in relation to peak time education trips.) Traffic counts were combined with forecasts from the National Transport Model to estimate the likely flows in 2030, with and without the housing development going ahead. Of the junctions studied, in four cases the additional traffic generated by the development would, by 2030, exceed the capacity of the junction:

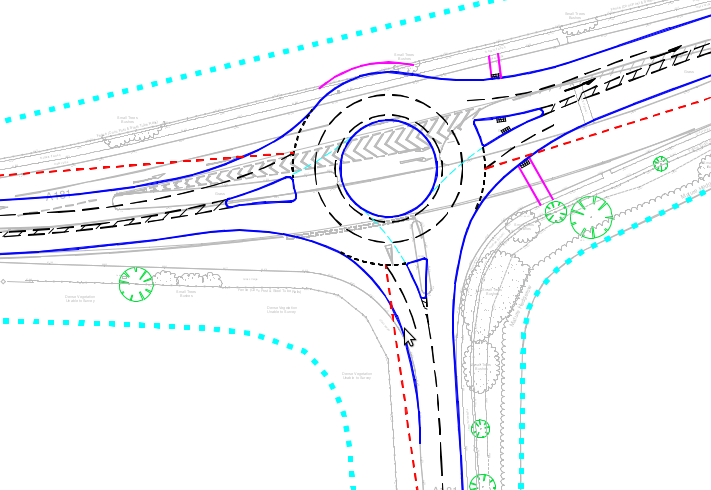

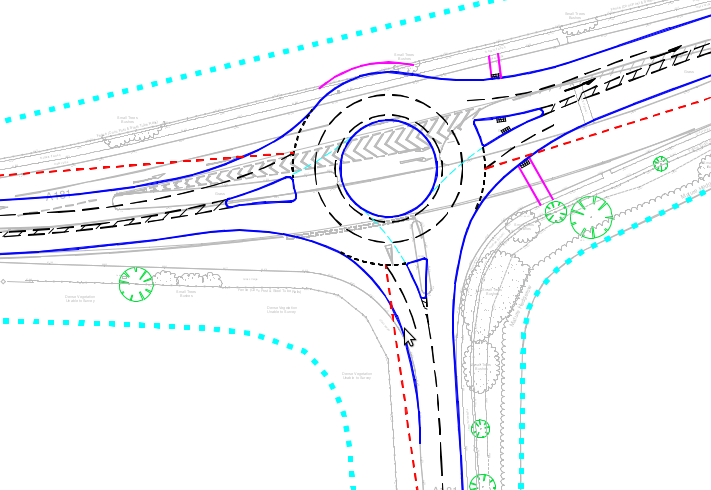

For three of these, the mitigation proposed is to convert the junctions to roundabouts, or to add traffic signals or extra lanes to accommodate the growth.

Proposed roundabout at the A181/B1283 junction to the east of the site

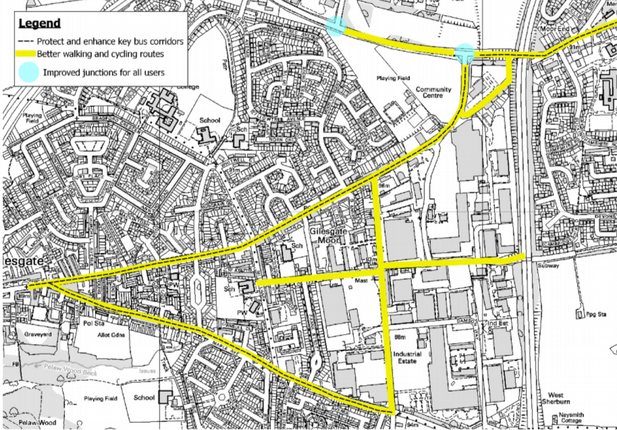

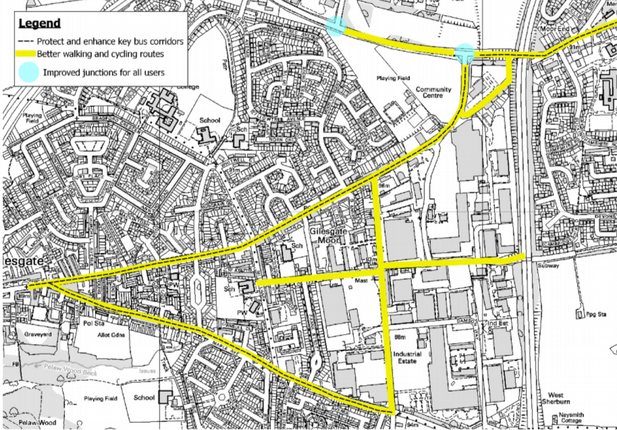

At the meeting of the A181 and the Sunderland Road there is no room to enlarge the junction, and instead the developer indicates a willingness to contribute funding towards walking, cycling and public transport improvements along the A181 and Sunderland Road corridors into Durham City, and the assessment refers to routes identified in the Durham City Sustainable Transport Delivery Plan. I have to confess that when helping to prepare the Trust’s responses to the application, I did not spot this offer of investment in sustainable transport in section 8.5 of the Transport Assessment. While detailed plans have been submitted for the remodelling of the other junctions, there are no plans covering walking or cycling improvements on the A181 or Sunderland Road. Perhaps the developer is relying on the Council’s preparation of the Local Cycling and Walking Infrastructure Plan (LCWIP) which is expected to be presented to the cabinet in June?

Map from Durham City Sustainable Transport Delivery Plan with roads requiring walking, cycling and public transport improvements highlighted.

Despite the lack of detail, the TA concludes:

Following the implementation of sustainable transport measures of these types, it is considered that the residual impact of the proposed development on the operation of the highway network will be immaterial.

There is no evidence given to support this view. The application lacks detailed plans, evidence or modelling of the alternatives to motor traffic growth. This sadly reflects the importance assigned to motor traffic flow in contrast to sustainable transport by most developers and local authorities. There is a whole industry built around the problems posed by growth in motor traffic, with specialist software, survey techniques, and design solutions which highways engineers will instinctively reach for. But remember! – the Sixth Carbon Budget requires us to steadily reduce the amount of car traffic year by year by about 3% for the foreseeable future. The National Transport Model, which the applicant draws on for the forecast growth, does not yet reflect this. It is a “predict and provide” model based on laissez-faire transport policies which are not equal to tackling the climate crisis.

The Transport Assessment acknowledges (para. 7.7.4) that “traffic growth forecasts at both a national and a local level have historically tended to significantly overestimate growth”. It also notes that changing patterns of work and employment, hastened by the pandemic, are likely to flatten the peak demand. But in order to come to a “robust” assessment, neither of these uncertainties have been factored in. Still less has the need to actually reduce, in absolute terms, traffic levels.

The result is that the planning application, as currently formulated, envisages large-scale works at two or three road junctions to accommodate traffic growth which the application acknowledges is likely to be overestimated – traffic growth which needs to be reversed to meet our climate commitments. These have been prioritised over unspecified improvements for sustainable transport, the effectiveness of which has not been quantified.

Planning policy and the climate emergency

If the Council is serious about prioritising sustainable transport, as it has claimed in various policy documents, then the planning authority should be requiring a much higher standard of analysis from developers, and the highway authority should take a sustainable-first approach to mitigation of the impacts. The expectation can be set by the Council at the pre-application stage.

Most development proposals have some downsides, and determining whether an application should be approved is a matter of balancing different policies and needs. To do this, planners and planning committees have to judge how much weight to give when an application does not fully comply with a policy by comparison with any benefits that will result. I would argue that in the context of the climate emergency, where we have to make a transition in transport “like none we have attempted before” (to quote Professor Greg Marsden), considerable weight needs to be given to the planning policies which favour sustainable transport.

Many developers quote from National Planning Policy Framework paragraph 109 which states that

Development should only be prevented or refused on highways grounds if there would be an unacceptable impact on highway safety, or the residual cumulative impacts on the road network would be severe.

The wording in earlier versions of the NPPF referred to “transport grounds” rather than “highways grounds” and developers and the Council sometimes still use the old wording. The change, however, was deliberate and significant. It signifies that development may be refused on various other transport grounds, such as poor provision for sustainable transport, without there necessarily being severe residual impacts on the road network.

What would a sustainable approach look like?

The initial focus should be on the Transport Assessment and any associated mitigations. Most Transport Assessments follow a common pattern, and a standard aspect to include is an assessment of the accessibility of the site by different modes. In the Bent House Lane application, five pages describe the current walking, cycling and public transport networks around the site, and another five pages access the accessibility of local amenities by these modes. The analysis is often quite superficial: for example, as with many other Durham City applications, the section on cycling is keen to mention National Cycle Network Route 14 with its connections to Darlington via Hartlepool and South Shields via Consett, but is silent on the lack of dedicated provision for realistic local journeys.

By contrast, forty-one pages of the main report cover the highway network and the assessment of the junctions. These are supplemented by another 300 pages of appendices which are entirely devoted to motor traffic surveys and modelling.

A sustainable-first approach would also include a qualitative assessment of the pedestrian and cycle network, and would recognise that existing provision may be sub-standard. This need not be any more onerous than the traffic surveys and modelling. For example, there is a simple junction assessment tool in the new government guidance, Cycle Infrastructure Design LTN 1/20 (p. 178), which could be applied to each junction a cyclist would have to pass through to reach the local amenities, schools and employment sites. Most of the junctions around Bent House Lane would score very badly.

Improvements to the walking and cycling infrastructure could then be proposed. The Department for Transport sponsored Propensity to Cycle Tool would be consulted, demonstrating the potential for 17% of commuter journeys to be cycled, given good-quality routes. Such routes might parallel the main road routes, but there is also the opportunity to give sustainable transport a significant advantage by providing short-cuts. For example, from Bent House Lane the Elvet area and the university campus at Mountjoy could be reached via riverside paths. Liaison with local schools might identify other barriers to sustainable travel noted in their school travel plans.

For public transport a simple table of the service frequencies and destinations would not be sufficient: there needs to be a demonstration that journey times would actually compete with alternative modes. Bus priority measures could then be proposed and funded. There would be evidence of engagement with public transport operators.

Conclusion

Planning applications are determined according to the local County Durham Plan, which itself accords with national planning policy, and the change of administration at County Hall does not change this. But the weight accorded to policies – what is judged important, and where compromise can be accepted – is to some extent a political decision. And it is absolutely the preserve of the Council as highways authority to judge what is acceptable in terms of transport mitigations. The applicant has demonstrated that there are transport impacts which require mitigation, and the new administration could insist that major works to increase motor traffic capacity at junctions should be the last, not the first resort.

By prioritising sustainable transport interventions, not only would a greater proportion of the new residents’ journeys be by sustainable modes, but other people would benefit from the improvements, in turn freeing up capacity on the surrounding road network and reducing the need for motor traffic growth to be accommodated. The aim should be to avoid the need to commit any funding to road “improvements” because these will become frozen assets (or white elephants) if we are successful in reducing demand in response to the climate emergency.

Further reading

If you are interested in more information on the Bent House Lane application, the Trust submitted an initial response to the planning application in January. Pages 4-6 summarise the transport objections, which are set out in detail on pages 13 to 35. A further response was submitted in March which covers public rights of way, road junctions and bus stops.

The full documentation can be found on the County Durham online planning application system by searching for reference DM/20/03558/OUT.

See our previous post on this topic.